![]()

A craft that has

almost completely disappeared from the rural districts within the last few years (early

1960s) is that of clog making. The origins of this simply constructed piece of footwear

are lost in the mists of antiquity, but clogs were certainly worn by rich and poor alike

in the middle ages. In later times they were widely worn both on the factory floors, in

mines and on the land, particularly in wales and the north of England. Although they may

still be found in the textile mills of Lancashire and Yorkshire, the clogging factory

still being fairly common in such towns as Huddersfield and Halifax, the old rural

clogmaker is now a rarity. In wales in 1918, for example, there were 65 specialised

clogmakers, excluding those who were also bootmakers and repairers; in 1963 there were

less than half a dozen working clogmakers. With the changes in fashion of the last few

years the clogmakers has become a rarity and only a few representatives of the craft may

be seen at work in Britain at a trade that demands considerable knowledge, not only of

leatherwork, but of woodwork as well. A craft that has

almost completely disappeared from the rural districts within the last few years (early

1960s) is that of clog making. The origins of this simply constructed piece of footwear

are lost in the mists of antiquity, but clogs were certainly worn by rich and poor alike

in the middle ages. In later times they were widely worn both on the factory floors, in

mines and on the land, particularly in wales and the north of England. Although they may

still be found in the textile mills of Lancashire and Yorkshire, the clogging factory

still being fairly common in such towns as Huddersfield and Halifax, the old rural

clogmaker is now a rarity. In wales in 1918, for example, there were 65 specialised

clogmakers, excluding those who were also bootmakers and repairers; in 1963 there were

less than half a dozen working clogmakers. With the changes in fashion of the last few

years the clogmakers has become a rarity and only a few representatives of the craft may

be seen at work in Britain at a trade that demands considerable knowledge, not only of

leatherwork, but of woodwork as well.Despite the gradual disappearance of the clog and its replacement by rubber boots, it is still a very practical piece of footwear, particularly for agricultural workers. With thick wooden soles and iron rims, the wearer's feet are kept well above the level of a wet floor and, since each pair is made to fit the feet of each individual customer, they can be extremely comfortable and warm. In the heyday of clogmakers there were two distinct types of craftsmen engaged in the trade. They were: 1/ The village clogmaker who made footwear for a local market. He made clogs for each individual customer, taking accurate measurements of each foot, and cutting the clog soles to the shape of a paper pattern, made according to those measurements. His work will be considered later (below).

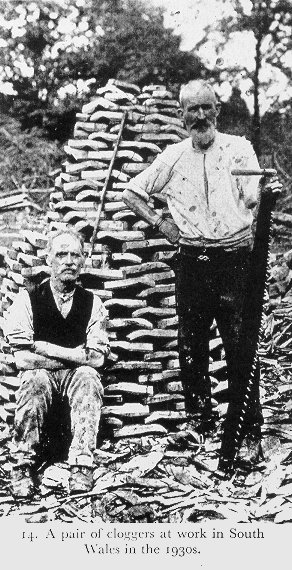

For clog sole making the craftsman requires a timber that does not split easily, but on the other hand, it must be relatively easy to shape. As clogs are used on wet factory floors, mines and muddy fields, the sole must be durable in water and completely waterproof. Tough, resilient willow which lasts indefinitely in moist conditions is occasionally used by north country craftsmen as is birch and beech, but in that area as well as in Wales nearly all the clogs are equipped with alder or sycamore soles. While many village clogmakers utilise sycamore, the itinerant cloggers, by tradition are craftsmen in alder. Alder, a riverside tree, grows best in good fertile soil, with running water near the roots. It grows profusely in favoured conditions, its seed being carried from one place to the other by the streams. The timber it produces is soft and perishable under ordinary conditions, for it contains a great deal of moisture. In wet places, however, it is extremely durable and for this reason alder is widely used for such specialised tasks as revetting river banks. It can only be harvested in the spring and summer months and must be left to season for at least nine months before it can be used. Clogging was therefore a seasonable occupation and gangs of a dozen or more craftsmen wandered from grove to grove, living a hard, tough life in roughly built temporary shelters. In Wales the clogger reckoned that the amount of money made from selling waste material as pea-sticks and firewood should be enough to buy all the food the gang needed while they worked in the woods.

The work with the clogger's stock knife was highly skilled and intricate. The knife

itself is made of one piece of steel, some thirty inches in length, bent to an obtuse

angle in the middle. The blade is some four inches deep and thirteen inches long and the

whole knife terminates in a hook. The Village Clogmaker

Unlike the clogger, the village craftsman used a great deal of sycamore. In the past Welsh clogmakers reckoned that a sycamore tree cut from the hedgerow produced far superior soles to those cut from a forest or plantation. The trees are felled and immediately converted into sole blocks; first with beetle and wedge, then with an axe and finally with the large stock knife. The process so far, is similar to that adopted by itinerant cloggers, and a few deft strokes with this guillotine-like stock knife soon reduces the blocks of wood to nearly the correct shape. In the case of the village clogmaker, however, measurements that are more accurate than the cloggers 'men's', 'women's', 'middles' and 'children's' are adopted, for the clogmaker measures the customer's feet accurately and transfers those measurements to a paper pattern. In many clogmaker's workshops, patterns representing the feet of generations of local inhabitants may still be found.

The leather uppers are again cut out in accordance with a paper pattern, the method of working being the same as clicking in bootmaking. Stiffeners are inserted at the heels, lace holes are cut and eyelets fitted and the assembled leather uppers are strained over a wooden last. It is tacked in place, hammered into shape and left in the last for a few hours to be moulded into the correct shape. Unlike a boot, the clog is removed from the last before assembling. Unlike the boot, too, the clog upper is not sewn to the sole, but nailed with short flat-headed nails. A narrow strip of leather is cut and placed over the 'unction of uppers and sole. Great care has to be taken to ensure that the nails used in assembling point downwards and are in no danger of damaging the wearer's feet. Replaceable grooved irons are nailed to the sole and heel; a bright copper or brass tip is tacked to the front and the clogs are ready for wear. With constant use and the replacement of irons at regular intervals a pair of clogs may last without resoling for at least twelve years. From: "Traditional Country Crafts" by J. Geraint Jenkins, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1965. Other references:

Unfortunately there are only a very small number of clog makers left from the many hundreds who traded in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Cloggers still trading include Trefor Owen, the Turtons (see picture), Jerry Atkinson, Walter Hurst, and Walkleys. There are however many old and modern films and videos of clog makers and clog dancers, and these are listed here: Videos, Tapes & Books. For information on Lancashire clog dancing see: Lancashire Clog Dancing |

![]()

Email: Chris Brady |

Top # Home | |