![]()

ContentsPREFACE - MADELEINE INGLEHEARN'THE HORNPIPE - OUR NATIONAL DANCE' - MADELEINE INGLEHEARN''THE HORNPIPE IN SCOTLAND' - JOAN FLETT'THE LANCASHIRE' - PAT TRACEY'GROUND, HORNPIPE, DUMP AND JIG: ENGLISH VERNACULAR KEYBOARD STYLE,

1530-1700'

|

| BIBLIOGRAPHY |

* Arne, Thomas - A 4th book of Hornpipes, 1760 ms. British Library

* Blasis, Caroo - The Art of Dancing, 1830, (trans. R. Barton), facsimile Dover Press

* Chappell, William - Popular Music of the Olden Time, Vol II

* Curti, Martha - The Hornpipe in the 17th century, Music Review XL/1 1979

* Daniel, George - Merry England, 1842

* Emmerson, George S. - A Social History of Scottish Dance, McGill Queens University Press 1972

* Fishar, J - collection of music for Cotillons, Minuets, Allemands and Hornpipes, c1773, ms in British Library

* Gallini, Giovanni-Andrea - A Treatise on the Art of Dancing, 1763, facsimile Broude Bros. 1967

* Grove, Lily - Dancing, 1895, Green & Co.

* Marsden, Thomas - A collection of Lancashire Hornpipes old and new, 1705, ms. British Library

* Marsh, Carol - French Court Dance in England 1706-1740, Ch. VI - unpublished Ph.D. dissertation 1985

* New Grove Dictionary of Music & Musicians - Hornpipe, review by Margaret Dean Smith, Vol VIII, Macmillans 1980

* Peele, George - Arraignment of Paris, 1584

* Price, Curtis - Music in the Restoration Theatre, UMI Research Press 1979

* Scott, E. - Dancing as an Art & Pastime, 1892

* Seymour, J. - Nancy Dawson' s Jests, 1761

* Tatler, The - issue no. 106, 1709

* Thompson & Son - 30 Favourite Hornpipes, 1760 , ms. British Library

* Walsh, John (pub) - 3rd Compleat Country Dancing Master, 1735, ms. British Library

* Walsh, John (pub) - 3rd Book of the most celebrated Jiggs, Lancashire Hornpipes, Scotch and Highland Lilts, etc. c.1731, ms. British Library

* Ward, John - The Manner of Dauncynge, Early Music IV/2 1976

* Wright, Daniel - An extraordinary collection of pleasant and merry humours 1715, ms. British Library

(©) Madeleine Inglehearn 1993

![]()

What is a HORNIPE? Curt Sachs, in his 'World History of Dance,' [1] notes that you never get a musical instrument named after a dance but that you do get dances named after musical instruments. He cites 'sarabande' - from zarabande, a national flute of Guatemala, 'piva' - a form of Italian bagpipe, tambourine and hornpipe. A 'hornpipe' was a single reed pipe with a horn mouthpiece, similar to the chanter of the bagpipes: it seems to have disappeared by the 16th century.

In old Scottish records there is often some confusion about the term 'hornpipe.' It was often used along with the term High Dance to denote a solo dance.

R. C. MacLagan, in his unpublished notes for his book Games and Diversions of Argyleshire,[2] wrote "Single dances - Hornpipes - such as 'Gille Challum' and 'am Bonaid Ghorm' were also in vogue and afforded great scope for competition." This is a reference to the Sword Dance and Blue Bonnets, a dance of varying form, and we would not regard these as hornpipes from the music to which they are danced. The term High Dance occurs very frequently and, although there are cases in which it is possible to identify a dance as a hornpipe, it is clear that it did often simply denote a solo dance. One well-known reference to the High Dance is that in the letters of Major Edward Topham[3]. Visiting Edinburgh in 1774 and 1775 he described the children's balls at which the dancing master "enlivens the entertainment by introducing between the minuets their High Dances, (which is a kind of double hornpipe) in the execution of which they excel perhaps the rest of the World. I wish I had it in my power to describe to you the variety of figures and steps they put into it. Besides all those common to the hornpipe, they have a number of their own, which I have never before seen or heard of; and their neatness and quickness in the performance is incredible: so amazing is their agility, that an Irishman, who was standing by me the other night, could not help exclaiming in his surprise 'that, by Jesus, he never saw children so handy with their feet in all his life.' "

We also have to be cautious about Scotch Measures. William Stenhouse in his Musical Illustrations (his notes) for James Johnson's The Scots Musical Museum[4] which Stenhouse re-edited after Johnson's death in about 1820, wrote 'The Flowers of Edinburgh … . The editor is creditably informed that the tune only became a fashionable Scottish Measure (a sort of hornpipe so called) about the year 1740.'

Scotch Measure was a term used in former times for a distinct type of tune.

Stenhouse is undoubtedly using the term, and the term hornpipe, in the musical sense but some writers use the term in the sense of 'to tread a measure'.

| HIGH DANCES |

The term High Dance refers to the nature of the elevation of the steps in contrast to the low gliding steps of older Basse Dances or low dances. This change in style of dance began in the 16th century in the Elizabethan age, when Elizabeth I encouraged her court to dance and was, herself, an energetic dancer. There is a well-known woodcut showing Elizabeth dancing La Volta in which she is being hoisted in the air by her partner.

Dancing masters often made up dances for their favourite pupils, especially for the children of the gentry, so that you find Miss So and So's High Dance or Mr. X's High Dance. Many High Dances are to be found in the music collections of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

In A Directory of Ball Music, advertised in the Edinburgh Caledonian Mercury in June 1800, there are eleven High Dances listed – Miss Bruce's Favourite High Dance, Mr. Hay's, Mr. Miller's and Miss Miller's High Dance, etc. These may not all have been hornpipes but at least some of them would have been. Another nice reference to a High Dance, indicating the elevated style of the steps, occurs in a letter written in 1814[5] in which a governess records " … she commenced a reel between two marble pillars … having just remarked that 'I must fancy this pillar, him and the other – any body you like,' … The reel finished, she began a high dance, which she went through with inimitable grace, ease, and spirit, finishing the whole by lightly leaping over a conversation stool."

We have the instruction for just one dance 'of this type - Miss Gayton's Hornpipe – but unfortunately we do not know anything of its history or of Miss Gayton herself.

The dance was taught by the Wallace family of Kilmarnock and the family had been dancing teachers from the middle of the 19'th century at least. The tune Miss Gayton's Hornpipe is also known as Miss Heaton's Hornpipe.[6]

| HORNPIPES |

The musical timing of tunes known as hornpipes has varied over the years. Writing in his Popular Music of the Olden Times in 1855 William Chappell noted, "All hornpipes in common time are of comparatively late date, - perhaps in no case earlier than the last century, and generally of the latter half. The genuine old English hornpipe was in triple time, simple or compound; and although, about the commencement of the last century, some were reprinted, and then marked 6/4 they are, nevertheless, in 3/2 time ... . I make these remarks because the manner of dancing the hornpipe has certainly been changed. The stage hornpipes of the latter half of the last century, and the steps taught by the dancing-masters within the last forty years to tunes in common time, cannot have agreed with the ancient country way of dancing."

An earlier writer, Charles Stewart[7], who was musician to Mr. Strange, a well-known Edinburgh dancing master; gives a classification of the different types of hornpipe. He has a section of 'treeble hornpipes' all in common time, a section headed 'double hornpipes' which are in 9/8 time and 'single hornpipes' which are all in 6/4 time. William Stenhouse in his Illustrations to the Scots Musical Museum noted 'The Dusty Miller.' "This cheerful old air is inserted in Mrs. Crockat's Collection[8] in 1709, and was, in former times, frequently played as a single, hornpipe in the dancing-schools of Scotland." He later notes, "These old tunes - Wee Totum Fogg - The Dusty Miller - Go to Berwick Johnnie - Mount your Baggage - Robin Shure in Har'est - Jocky said to Jenna, etc., etc., have been played in Scotland, time out of mind, as a particular species of 'the double hornpipe.' "

The late James Allan, piper to the Duke of Northumberland, assured the present editor that this peculiar measure originated in the borders of England and Scotland. "Playford has inserted several of them in his D.M. ... " This is reference to The Dancing Master published by John Playford which ran to many editions from 1651. Henry Playford in Apollo's Banquet ... [9] 1690, gives a 'Scotch Hornpipe' in 9/4 time, and William Chapell, who later owned the book, added a note in ink that this tune was The Souters of Selkirk.

As far as the origin of the hornpipe dance is concerned various writers agree that its country of origin is Britain with some stating England specifically. Giovanni Gallini, dancer and sometime manager of Her Majesty's Opera House in the Haymarket, wrote in his A Treatise on the Art of Dancing, London 1765, "In Britain, you have the hornpipe, a dance which is held an original of this country. Some of the steps of it are used in the country dances here, which are themselves a kind of dance executed with more variety and agreeableness than in any part of Europe... ." Sir John Hawkins in A General History of the Science and Practice of Music, London 1776, says "That the HORNPIPE was invented by the English seems to be generally agreed; ... The measure of the Hornpipe is triple time of six crotchets in a bar, four whereof are to be played with a down, and two with an up hand." Alexander Campbell, in his notes to a long poem called The Grampians Desolate, published in Edinburgh in 1804, wrote "The hornpipe of the ENGLISH, the Scottish Measure of the Lowlanders, the Reel of the Highlanders, and the Jig of the Irish, are still preserved, and danced with that life and spirit peculiar to each nation or province to which those dances belong."

As we come to wonder what the hornpipe actually looked like we are tantalized and frustrated by a letter in Notes and Queries, vol. 12 1855. A frequent contributor to the publication, a certain W.J. whom we believe to be William Jerdan of Dunse, wrote "A century and two or three years ago, the dancing master of a southern Scottish town wrote out manuscript instructions for his pupils, of whom my father was one: and a copy is now before me which may suggest some musical and other minor matters relating to the amusements of our progenitors, curious enough for a notice in 'N.&Q.'. It is entitled 'The Dancing Steps of a Hornpipe and Gigg.' As also Twelve of the Newest Country Dances, as they are performed at the Assemblies and Balls. All Sett by Mr. John M'gill for the use of his school, 1752."

I do not know that the dancing instructions for sixteen steps in the hornpipe, and fourteen in the gigg, would be very intelligible now-a-days; seeing that in the former, the second, third and fourth steps are 'slips and shuffle forwards', 'spleet and floorish (flourish?) backwards', 'Hyland step forwards', and there are elsewhere directions to 'heel and toe forwards', 'single and double round step', 'slaps across forward', 'twist round backwards', 'short shifts', 'back hops', and finally, 'happ forward and back' to conclude the gigg with éclat.'

Alas, we hunted high and low for the MS without any luck. However, we are given a glimpse of a lively and vigorous style of dancing and can guess how some of the steps were performed. We can also assume that they would have been widely known in Scotland at that time.

The hornpipe was obviously extremely popular at the end of the 18th century. In the 1760s the firm of C & S Thompson at addresses in St Paul's Churchyard, variously given as at the'Violin and Hautby' and as '75 St Paul's Churchyard,' published three collections of Favourite Hornpipes[10]. The first two contained thirty and the third contained one hundred and twenty! All "as performed at the Public Theatres."

The second collection contained roughly equal numbers of tunes in Common and 3/2 time, about fourteen in 6/8 time, one in 2/4 and one in 9/8 time. Among them were 'Aldridge's Hornpipe' and 'Strange's Hornpipe.' Both Strange and Aldridge being dancers on the Edinburgh and London stage, and, in Aldridge's case, also in Dublin.

Alexander McGlashan in A Collection of Scots Measures, Hornpipes, Jigs; Allemands, Cotillons and the fashionable Country Dances, Edinburgh 1781, gives eight dances "as danced by Aldridge", including Highland Laddie, The Corn Cutters, a hornpipe and an allemande. The Scotch Measures which William Stenhouse referred to as a "sort of hornpipe" are tunes in common time with a crotchet rhythm, with two main beats and two weaker beats in each bar. They are much more 'bouncy' than reels.

A typical example is Petronella and it is of interest that stepping in hornpipe style called 'treepling' was in use in the dance 'Petronella' up until at least 1914. Treepling is presumably derived from 'treble' movements and the steps known in East Lothian, Roxburghshire and West Berwickshire included trebles, double trebles single and double flatters and the men used a succession of trebling movements which they knew as the 'Jacky Tar' step[11]. [Petronella with 'treepling' was a dance in the Reading Cloggies' repertoire in the 1980/90s - CJB].

Tunes often appear under different names and the tune Dusty Miller, which William Stenhouse had noted as appearing in Mrs Crockatt's Collection in 1709, appears earlier in the Blaikie MS of 1692 under the title Binny's Jig. It appears as Dusty Miller in Walsh's Compleat Country Dancing Master, published in London in 1731 and in his Caledonian Dances in 1733. In 1794, George Jenkins, a dancing master in London, who had previously practiced in Edinburgh, composed a tune called Jenkin's Dusty Miller which seems to imply that he danced a dance called Dusty Miller but to his own music. The only instructions for the dance known to us appear in a MS collection of dances written Aberdeenshire in 1841. It was written by Frederick Hill who was born in London in 1824 but spent the greater part of his life in Alford in Aberdeenshire where he learnt the dances, probably from the 'Myren' mentioned in his book, for the Myron family of dancing teachers was still remembered in the neighbourhood in the late 1950s. In addition to Dusty Miller the MS contains several other interesting dances. There is 'Wilt thou go to the barracks, Johnnie' which is possibly a corruption of 'Go to Berwick, Johnnie' mentioned by Stenhouse as one of the old 3/2 hornpipes. It also contains a 'Scotch Measure' and the 'Trumpet Hornpipe.' A dance entitled Scotch Measure has been published by several authors as a dance for two but there does not seem to be any evidence for this. It is possibly a misinterpretation of the term 'double hornpipe' used in the past for the music. Of the Trumpet Hornpipe we only know the tune elsewhere[12]. The above mentioned MS is still in the possession of descendants of Frederick Hill.

We come across named hornpipes in newspaper

reports of Edinburgh theatre performance. In the 18th and early 19th centuries an

evening's entertainment usually consisted of a play, often on the serious side, followed

by a farce. In the interlude between the two there would be a singer or a dancer. So, in

1819, when Mrs. Siddons was appearing at the Theatre Royal in Edinburgh, the "Junior

Miss Worgman" performed her "Pas Seul to the National Air of The Blue Bells of

Scotland," and Mr Swann introduced his "much admired Naval Hornpipe." Mr

Swann was the Ballet Master and principal dancer and, on January 30 of that year a benefit

evening was held for him at which he danced his "much admired Fetter Hornpipe - 'A

Scotch dance.' " In February there was a Skipping Rope hornpipe by Miss M. Nichol and

a Clog Hornpipe by Mr. Bristow. At the end of February Miss Nicol moved over to The

Pantheon where she performed a "nautical double Hornpipe" with a Miss Perry and,

in March at The Pantheon, Mr. Fielding danced "A Sailor's Hornpipe." London

theatre playbills show even earlier references to hornpipes. In an article in 'The Folk

Music Journal,' 1970[13], George Emmerson notes a "Hornpipe by a

Gentleman" at Drury Lane in 1713. In 1730 at Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre there was a

"Grand Comic Dance of Sailors" in which a French dancer, Salle, performed a

"Hornpipe in the character of a Boatswain." The hornpipe was also popular in

America where the dancer John Durang was famous for his hornpipe dancing, including a

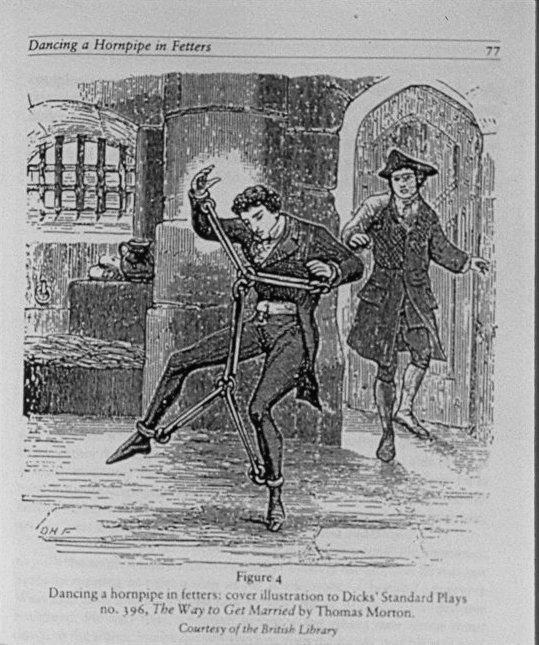

'Sailor's Hornpipe,' in the 1780-1790s. The reference to the Fetter Hornpipe as a 'Scotch

dance' is interesting. We know of no description of it at that period in Scotland but in

late Victorian times a London dancer, Joseph Cave, performed a hornpipe wearing leg and

wrist irons and chains. There is an illustration of a dancer wearing rigid fetters in the

text of a play printed sometime after 1883 but the text notes that the play The Way to

Get Married, by Thomas Morton, had been performed at the Haymarket Theatre in 1828

which is ten years after the Fetter Hornpipe had appeared in Edinburgh. It is possible

that this solo dance had its origin nearly a hundred years earlier on the London stage. In

1728 John Gay's ballad opera The Beggar's Opera included "A Dance of Prisoners

in Chains, &c.". By 1830 this group dance had been replaced by a solo dancer

performing in fetters[14]. There is another hornpipe which was performed in

Scotland, namely the Cane Hornpipe, which may just possibly have had some connection with

the most popular hornpipe of all - the Sailor's Hornpipe. We know of just one reference to

this, in a small ballroom guide written by J. Scott Skinner, one of the best known

musicians and dancing teachers in Scotland. He recalls a number of solo and exhibition

dances which were once popular but had either disappeared or were only performed

occasionally, including the Cane Hornpipe.

We come across named hornpipes in newspaper

reports of Edinburgh theatre performance. In the 18th and early 19th centuries an

evening's entertainment usually consisted of a play, often on the serious side, followed

by a farce. In the interlude between the two there would be a singer or a dancer. So, in

1819, when Mrs. Siddons was appearing at the Theatre Royal in Edinburgh, the "Junior

Miss Worgman" performed her "Pas Seul to the National Air of The Blue Bells of

Scotland," and Mr Swann introduced his "much admired Naval Hornpipe." Mr

Swann was the Ballet Master and principal dancer and, on January 30 of that year a benefit

evening was held for him at which he danced his "much admired Fetter Hornpipe - 'A

Scotch dance.' " In February there was a Skipping Rope hornpipe by Miss M. Nichol and

a Clog Hornpipe by Mr. Bristow. At the end of February Miss Nicol moved over to The

Pantheon where she performed a "nautical double Hornpipe" with a Miss Perry and,

in March at The Pantheon, Mr. Fielding danced "A Sailor's Hornpipe." London

theatre playbills show even earlier references to hornpipes. In an article in 'The Folk

Music Journal,' 1970[13], George Emmerson notes a "Hornpipe by a

Gentleman" at Drury Lane in 1713. In 1730 at Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre there was a

"Grand Comic Dance of Sailors" in which a French dancer, Salle, performed a

"Hornpipe in the character of a Boatswain." The hornpipe was also popular in

America where the dancer John Durang was famous for his hornpipe dancing, including a

'Sailor's Hornpipe,' in the 1780-1790s. The reference to the Fetter Hornpipe as a 'Scotch

dance' is interesting. We know of no description of it at that period in Scotland but in

late Victorian times a London dancer, Joseph Cave, performed a hornpipe wearing leg and

wrist irons and chains. There is an illustration of a dancer wearing rigid fetters in the

text of a play printed sometime after 1883 but the text notes that the play The Way to

Get Married, by Thomas Morton, had been performed at the Haymarket Theatre in 1828

which is ten years after the Fetter Hornpipe had appeared in Edinburgh. It is possible

that this solo dance had its origin nearly a hundred years earlier on the London stage. In

1728 John Gay's ballad opera The Beggar's Opera included "A Dance of Prisoners

in Chains, &c.". By 1830 this group dance had been replaced by a solo dancer

performing in fetters[14]. There is another hornpipe which was performed in

Scotland, namely the Cane Hornpipe, which may just possibly have had some connection with

the most popular hornpipe of all - the Sailor's Hornpipe. We know of just one reference to

this, in a small ballroom guide written by J. Scott Skinner, one of the best known

musicians and dancing teachers in Scotland. He recalls a number of solo and exhibition

dances which were once popular but had either disappeared or were only performed

occasionally, including the Cane Hornpipe.

| THE SAILOR'S HORNPIPE |

The Sailor's Hornpipe enjoyed amazingly widespread popularity - sometimes under the alternative names of Naval Hornpipe or Jacky Tar. It was taught by dancing masters all over Scotland from the Borders to the Highlands and Western Isles and was frequently performed at Highland Games from the Highland Gathering at Luss, in Dumbartonshire, in 1893, up to modern times. Dancing masters in both Scotland and England usually included 'character dances' in their repertoires and taught children tambourine dances, gypsy dances, jocky dances, skipping rope and hoop dances. Both in England and in Scotland a Blackamoor's Dance was taught and, at Mr Lowe's ball in Inverness in 1848 the "Boat's crew of jolly tars, arrayed in appropriate costume, performed their hornpipe in gallant style."[15]

A similar dance for a group of dancers was a Nautical Caprice taught by Mr Cowper of York. His family later moved to Whitehaven where his descendants continued to teach until very recently. One odd reference to the dance under the name of Jacky Tar occurs in a book of Puirt-a-Beul[16], the mouth music used for dancing when no musical instrument was available and also sung during work, for example when women worked at fulling cloth they would sit round the board on which they pounded the cloth and sing. A song was collected by Dr. Keith MacDonald under the title Ruidhle Calleach Eachainn Mhoir or Cawder Fair which tells the story of two women dancing a reel who excite the envy of an old woman, who remarks that she was an excellent dancer of Jacky Tar in her youthful days. Andrew MacIntosh[17] commenting on English and Gaelic words to strathspeys and reels has a note about this tune - "Jacky Tar is a hornpipe, and a solo dance, and a most unusual one for a woman to engage in."

J Scott Skinner, his The People's Ballroom Guide says, "No exhibition dance is more popular than the Sailor's Hornpipe or Jacky Tar." He gives ten steps for what he calls 'one set of instructions': it includes the action of 'rope pulling' that is always included in the dance today. His notes on the dance make fascinating reading. The passage is headed The Hornpipe and he says "Hornpipes are of English origin, and seem to have been called after an obsolete instrument of which only the name remains." He then continues in inverted commas implying that he is quoting someone, "It is consistent with our national characteristics as a maritime nation that a native dance should be a sailor's dance. Hornpipes and jigs are old favourites in the service, and by no section of the community are they danced with more sprightly springiness, joyous activity, or keener enjoyment. As an argument for the health promoting properties of dancing, the Hornpipe must be accepted as a practical instance to the point. Captain Cook, for example, proved that dancing was most useful in keeping his sailors in good health on their voyages. When the weather was calm, and there was consequently little employment for the sailors, he made them dance, the hornpipe for preference, to the music of the fiddle; to the healthful exertion of this exercise the great circumnavigator attributed the freedom from illness on board his ship." He goes on to quote Robert Burns:

"But hornpipes, jigs, strathspeys, and reels

Put life and mettle in their heels."

He comments that "The Hornpipe had been early naturalised north of the Tweed, and is treated by our eighteenth century bards as a kind of native dance ... Hornpipe tunes are lively and decisive in character. The best known is the College Hornpipe, Chappell, in his Popular Music of the Olden Time, also noted 'The College Hornpipe ... is the tune to which an old sailor's song, called Jack's the Lad, is sung.' "

David Anderson of Dundee, another of the very well-known teachers, in his small ballroom guide for 1899[18] gives instructions for the Sailor's Hornpipe with twelve steps and a quick time finish and stated that the tune used could be Jack the Lad, Jack o' Tar' or Sailor's Hornpipe. Among all the High Dances listed in the Edinburgh Caledonian Mercury in 1800 there was also "Sailor's Dance in Capt. (C time)."

Did sailors actually dance THE Sailor's Hornpipe as we know it today? It seems unlikely. They would obviously dance solo dances of some sort - they would not have danced social dances, i.e. those for a mixed company. [Actually there is some photographic evidence of sailors on board sailing ships dancing social dances - one partner taking the role of the man, with his 'partner' the role of the woman. There would be at least one musician on board a sailing ship, usually a fiddle player who was emplpoyed to lead the sea-shanty work-songs; he was often an ex-sailor who had likely suffered a serious fall from the rigging and who was otherwise physically disabled - CJB] Emmerson, in his article in The Folk Music Journal, gives as evidence for Captain Cook's sailors dancing Notes upon Dancing, Carlo Blaise, London 1847, and also quotes a reference from the journal of a young Scottish lady traveling to the West Indies in 1774[19]. "The effect of this fine weather appears in every creature, even our Emigrants seem in great measure to have forgot their suffering ... and if we had anything to eat, I really think our present situation is most delightful. We play at cards and backgammon on deck; the sailors dance horn pipes and Jigs from morning to night." This is another instance when hornpipe and jig may have simply been used to indicate a solo dance.

There is a certain amount of evidence on the evolution of the dance as a 'character' dance. There is an early print[20] of an ex-sailor, T. P. Cooke, who became a dancer and stage manager in London theatres in the 1820s. He became famous for his dancing of hornpipes and introduced them into most of the plays he produced. In the print he is shown dressed as a sailor in a play called Black E'ed Susan and is flourishing a drawn sword. In 1835 a cartoon by George Cruikshank entitled 'The Sailor's Hornpipe' shows a small boy at a dancing lesson performing a dance with a small stick held behind his back and supported by the little finger of one hand[21]. It may be that the stick was a substitute for a sword in the same way that Scottish teachers used wooden sticks as a substitute for swords when teaching the Sword Dance Gille Callum.' However, interesting material has been collected in France by Yves Guillard[22] which brings together the use of a stick, or cane, the tune Sailor's Hornpipe and the steps of Durang's hornpipe. In the Sarthe district around Le Mans he has found great similarities between the local dances and the solos and quadrilles of Scotland[23]. This is not surprising as the common source for many of the steps is classical dance and many of the early stage dancers in Britain were French or were trained in France. The other similarity lies in the fact that dancing teachers in both countries, in recent times, were often ex-army and had learnt their exhibition dancing in the army. One of the most interesting dances is called L'Anglaise and is danced to the tune The Sailor's Hornpipe (College Hornpipe). In former times it could last anything from twenty to thirty minutes and is danced with a bamboo stick held behind the back and supported by the little finger of one hand - exactly like the small boy in Cruikshank's cartoon. Some of the steps are similar to those in Durang's hornpipe. The dance had great importance as it was the dance which had to be performed and judged when a dancer applied for his 'brevet de maître de dance,' his teaching certificate. The bamboo cane became the 'symbol' of the dancing master and appears on the 'brevets' and in early photographs of dancing masters. One cannot help wondering if the Cane Hornpipe mentioned by Scott Skinner had any connection with this usage.

In Britain the use of a cane disappeared and miming actions - climbing the rigging, pulling ropes, looking for ships, etc., were introduced in the latter part of the 19th century. Up until 1805 a boatswain's 'badge of office' was a bamboo cane tipped with twine with which he disciplined the sailors. This was known a 'starter' and was used across the backs of the sailors. In 1805 the practice of 'starting' was banned by the British Admiralty although it did continue unofficially for some years[24]. Yves Guillard suggests that after banning of 'starting,' the cane would no longer have been used as a symbol in the Sailor's Hornpipe and that miming movements were then introduced in its place.

| CLOG DANCING |

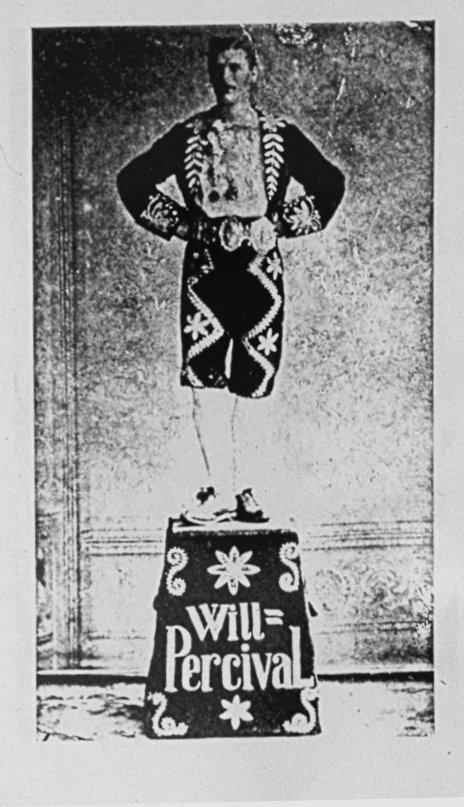

Clogs were once worn all over Britain right up until the Second

World War and clog dancing probably started on the street corner where young people would

gather and strike sparks from the cobbles with the iron rims on the soles of their clogs.

It was popular among men in the pubs where the landlord would often provide a prize of a

pair of clogs or a pint of beer for the dancer who could dance the greatest number of

steps. In a crowded pub the noise was the important thing, the beating of the steps to the

music. The dancing moved onto the Music Hall stage where performers like Charlie Chaplin,

Dan Leno and the [Five - CJB] Sherry Brothers danced as part of their acts.

Competitions for the 'World Championship of Clog Dancing' took place at which the judges

sat under the stage to judge the beat to the music. Sometimes the Music Hall dancer

would perform on a small pedestal, about a foot square and quite high off the floor –

a natural progression from dancing on a bar table.

Clogs were once worn all over Britain right up until the Second

World War and clog dancing probably started on the street corner where young people would

gather and strike sparks from the cobbles with the iron rims on the soles of their clogs.

It was popular among men in the pubs where the landlord would often provide a prize of a

pair of clogs or a pint of beer for the dancer who could dance the greatest number of

steps. In a crowded pub the noise was the important thing, the beating of the steps to the

music. The dancing moved onto the Music Hall stage where performers like Charlie Chaplin,

Dan Leno and the [Five - CJB] Sherry Brothers danced as part of their acts.

Competitions for the 'World Championship of Clog Dancing' took place at which the judges

sat under the stage to judge the beat to the music. Sometimes the Music Hall dancer

would perform on a small pedestal, about a foot square and quite high off the floor –

a natural progression from dancing on a bar table.

In Scotland this form of dancing was taught in the early part of this century [i.e. the 20th c. - CJB] right across the country. It was taught by dancing masters and, because it is an easy thing to do on your own, many people could perform it within living memory. We found, for example, that lads in the coalmines in Wigtonshire would step on the metal plates at the bottom of the mine shaft where the hutches of coal were turned round. In the Lake District, too, we found farmers would dance in the shippon on a cold day to keep their feet warm, old ladies would have remembered the steps because they would have been persuaded to dance at family parties and at the 'old folks' do' held each year in Ambleside ninety year olds would get up and step[25].

There were various hornpipes simply named 'clog hornpipes.' In Fife a well-known teacher, Mr William Adamson, and [also a] Mr Thomas Shanks in Wigtonshire, taught various dances including the popular Liverpool Hornpipe and the Lancashire Hornpipe - probably made famous by Music Hall artists appearing at local theatres. When these dances were performed on the stage or at the dancing masters 'balls' which concluded a season of classes and at which the pupils showed off their skills, the dancers very often had small bells fitted under the instep of their clogs or sometimes a coin or small stone - a 'chucky stane' was placed in a hollowed out heel. Although women danced on the Music Hall stage amongst the general populace younger girls would learn to dance but, as they grew older, they would tend to give it up - for two reasons, it was not 'done' for girls to frequent pubs and, also, in the days before bras it became uncomfortable to dance as their busts developed. The various clog hornpipes are once again popular, amongst both sexes, in the upsurge of interest in step-dancing and we pay tribute to all the dancing masters who have made this possible.

| REFERENCES: |

1. Sachs, Curt, World History of the Dance, New York 1937.

2. MacLagan, R.C., Unpublished notes in the library of the Folk-Lore Society.

3. Topham, Major Edward, Letters from Edinburgh, Written in the Years 1774 and 1775, Edinburgh 1776.

4. Stenhouse, William. (Ed.), Museum Illustrations, printed c1820 but not published until 1839 in a new edition of James Johnson's The Scots Musical Museum, edited by David Laing.

5. Bond, Elizabeth, Letters of an English Governess etc., London 1814.

6. Ashman, Gordon (Ed.), The Ironbridge Hornpipe, Northumberland 1991.

7. Stewart, Charles, A Collection of Strathspeys, Reels, Giggs, etc., Edinburgh c 1798 - 1801.

8. Crockat MS. This a music book dated 1705 and it is listed in J. T. Surrenne, (Ed.) The Dance Music of Scotland a collection of all the best REELS and STRATHSPEYS, both of the Highlands and Lowlands FOR THE PIANOFORTE, Glasgow 1841. We are indebted to Mr. E. J. Nicol for this reference.

9. Playford, Henry, Apollo's Banquet …, London 1690.

10. a) Thirty Favourite Hornpipes which are now in vogue and performed at the Public Theatres. Printed for Thompson and Son at Violin and Hautboy, St Paul's Churchyard.

b) As above, Books 1 – 4. Printed for C. and S. Thompson in St Paul's Churchyard.

c) Thompson's Compleat Collection of 120 Favourite Hornpipes as Performed at the Public Theatres. Printed for C. and S. Thompson at 75 St Paul's Churchyard. From internal evidence the date of a) appears to be c1760.

11. Flett, J.F. and T.M. Traditional Dancing in Scotland, London 1964 and, in paperback, 1985.

12. Darlington, Wilf, 'The Trumpet Hornpipe,' Folk Music Journal, vol.6 no.3 1992.

13. Emmerson, George S. 'The Hornpipe,' Folk Music Journal, vol.2 no.1 1970.

14. Bratton, J.S., 'Dancing a Hornpipe in Fetters', Folk Music Journal, vol. 6 no.1 1990; and also Correspondence in Folk Music Journal - vol.6 no.2 1991. Barlow, Jeremy. Correspondance in Folk Music Journal, vol.6 no.2 1991

15. Inverness Courier, October 3 1848.

16. MacDonald, K.N., Puirt-a-Beul, Glasgow 1901.

17. MacIntosh, A., 'English and Gaelic Words to Strathspeys and Reels,' Gaelic Society of Inverness, Trans. vol.20 1912 - 1914.

18.Anderson, David, Ball-Room Guide, Dundee 1899. This is in a collection of small ballroom guides in our possession. It also includes several copies of J Scott Skinner's The People's Ballroom Guide, Dundee and London c1905.

19. Andrews, E. W. (Ed.), The Journal of a Lady of Quality in 1774-1776, Yale 1921.

20. Bratton, J. S., op. cit.

21. Moore, Lilian, Images of the Dance, Historial Treasures of the Dance Collection 1581 - 1861, ... New York 1965. We are indebted to Yves Guillard for this reference and for that to the French dancer, Salle, and for all the information about 'starting' in the British Navy.

22. Guillard, Yves, Dancez, Sarthois! Cénomane, no. 15, Le Mans 1984. Danses de caracteres en Sarthe, tome 1, la tradition Bone, Le Mans 1987.

23. Guillard, Yves, Le Quadrille tel qu'il se dansait a ses origines, Le Mans 1988. 'Early Scottish Reel Setting Steps and the Influence of the French Quadrille,' Dance Studies, vol.13, Centre for Dance Studies, Jersey 1989. Les anciens Pas de Reel ecossais et l'influence du Quadrille français, Le Mans 1990.

24. Kemp, Peter, The British Sailor, 'A Social History of the Lower Decks, London 1971.

25. Flett, J.F. and T.M., Traditional Step-Dancing in Lakeland, [EFDSS,] London 1979.

=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-==-=-=-=

(*) Professor and Mrs. Flett spent over twenty years, until Professor Flett's early death, at the age of fifty two, in 1976, studying the literature and oral history of the social and solo dances of Scotland and the North West of England. Their book "Traditional Dancing in Scotland," published in 1964 by Routledge and Kegan Paul and re-issued in 1985 in paperback, is the definitive study of traditional social dancing. After Professor Flett's death their research into the step-dancing of Cumbria was published by the English Folk Dance and Song Society in "Traditional Step-Dancing in Lakeland" in 1979. A book on the solo dances of Scotland has been completed by Mrs. Flett but awaits a publisher. [And has now been published as "Traditional Step-Dancing in Scotland" - CJB]

(©) Joan Flett 1993

![]()

My main interest in the Hornpipe is centered on Lancashire clog dancing of the 19th and 20th centuries. Two strands of Hornpipe are involved - the even 4/4 rhythm of "Soldiers Joy" for example, and the uneven, or dotted rhythm of "The Trumpet Hornpipe". Each rhythm is associated with its own distinctive style of stepping.

| The even 4/4 rhythm |

The first of these, the old Lancashire heel and toe style, danced to the even rhythm, is the earliest known style of clog dancing. In the form it has come down to us, it is essentially a product of the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and 19th centuries which made Lancashire the centre of the cotton industry and the first county to employ its workers in large, purpose built factories.

The change in the lives of the people was traumatic. From working small farms and weaving their own cloth in their own homes, they were forced, for economic reasons, to go out to work, share the working day under the same roof as their neighbours and stand at their looms for twelve hours and more each day. The damp Lancashire climate, which kept the cotton threads supple, and the cold stone floors added to their problems. Their prime need was for strong, waterproof footwear and they found the answer in the countryman' s clog.

Country clogs were made for use on the land and, like today's wellies [Wellington boots], were kicked off at the door. They were made of stout leather uppers nailed to thick wooden soles on to which bands or rims of iron were fixed to protect the wood. They were heavy and loose fitting and, to quote my grandfather, "weighed a ton." Yet it was in clogs like these that the cotton workers developed their distinctive style of clog dancing.

Information about early clog dancing comes to me primarily through my grandfather and his contemporaries, though support has come from other sources, such as the "folk" memories of people I have met through dancing.

My grandfather was born in East Lancashire in 1856 and learnt clog dancing from the men in the area while he was still a young boy. They, in turn, remembered the older dancers and passed on their stories which my grandfather related to my mother when he taught her the steps.

The tradition is that clog dancing was sparked off by people standing at their looms, rattling their feet to keep warm, the more rhythmic among them dancing to the rhythm of the looms themselves. (Weavers were still tapping at their looms in this way in the 1930's). The rhythm of the looms also suggested the rhythm of the music, and there was no shortage of people who could get a tune out of a fiddle or pipe to accompany the dancers. [Listen at: Gateshead Garden Festival - CJB.]

Clog dancing seems to have spread rapidly. In the early part of the 18th century, villages were isolated, and inward looking and people provided their own entertainment. Most families had someone who could play an instrument or sing a song, and clog dancing burst on to their scene as something of a novelty. It had the great advantage that it required no extra expense as people danced in their working clogs. By 1850 every village had its champion clog dancer.

The style of the dancing was dictated by the clogs themselves. They were heavy and loose-fitting and slipped off at the ankles. In order to keep them in place, the dancers developed a flat foot style and used their heels as much as their toes to make the sounds, circling their feet outwards as they did so. The rhythm of the machinery runs through the stepping and the actions of the looms inspired some of the steps. When I visited Quarry Bank Mill at Styal in Cheshire, I had an opportunity to try dancing to the rhythm of the looms. The Mill, a former cotton factory, has been restored by the National Trust. It is far grander than any of the Lancashire mills I remember, but, during the restoration, looms were brought in from East Lancashire to set up the weaving shed. The day I visited, a man was operating 4 looms, the number usually operated, so I put on my clogs and danced. The stepping just fell into place with the rhythm of the machinery.

The basic rhythm of the dancing is a rather relentless driving rhythm which is punctuated by pauses and accentuated by occasional stamps to create patterns of sound. Tunes such as "Soldiers Toy" have the same relentlessness, but the all time favourite has been "Navvy on the Line", widely known as "The Clog Hornpipe". In tunes such as these, basic steps and patterns match the music note for note.

| The uneven or dotted 4/4 |

The second style of clog dancing associated with Lancashire is danced to uneven or dotted 4/4 hornpipe tunes such as "The Trumpet Hornpipe", "Steamboat" and "Click go the Shears", all played to a jolly bouncy rhythm.

This style is danced with the basic stepping on the toes, with the heels reserved for special effects. It is essentially "high" dancing, as opposed to the "ground" dancing of the old Heel and Toe.

Until the middle of the 18th century, Hornpipes were in triple time, but from the 1760's they appeared in common time. George Emmerson, who has condensed so much information for us on the Hornpipe, points to the possibility that Thomas Arne might have been responsible for the change of irection when, in 1760, he composed a "New Hornpipe" for Mrs. Vernon, a celebrated dancer, to perform to at Covent Garden. A successful performance would have alerted all dancers to the new hornpipe, and the fact that after this time there was a proliferation of hornpipes in 4/4 even rhythm, named after professional dancers - "Fishar's Hornpipe," "Aldridge's Hornpipe," Durang's Hornpipe," - suggests that something new had caught their attention.

Although the rhythm was akin to that used by the Lancashire Heel and Toe dancers, professional performers tended to dance "high," stepping on their toes and wearing neat fitting shoes. Modern tap dancing, which uses similar rhythms, is also danced on the toes.

As towns expanded with the growth of the cotton industry, troupes of itinerant performers came into East Lancashire. They set up their booths, rented rooms and shops, and gave several performances before moving on to the next town. My grandfather and his contemporaries always said that it was their people coming into the cotton areas who saw the potential of the clog as a dancing shoe. This is, at least, a possibility.

When travelling performers and locals congregated in the hostelries at the end of the day, there was music and dancing, with the local clog dancers showing off their steps. According to my grandfather, this always caused a stir and much laughter when the professionals borrowed the clogs and tried to dance in them. He said they used to "clump about" with the clogs "flying all over," but they could not dance in them because their style of dancing was different. They also, of course, danced in shoes. However, these travelling performers saw the potential of the clog as a dancing shoe and they could call on theatrical shoemakers to make tight fitting, lightweight clogs especially for dancing. All travelling performers hoped to get the big break and go on to the stage. Among those who made it, some achieved it by dancing in wooden soled clogs, and clog dancing became the craze of the late 1870's, 80's and 90's.

Professional clog dancers were not bound by traditional rhythms. They danced to hornpipe, jig, reel, waltz, etc., yet the dominant rhythm on stage at this time seems to have been the 4/4 dotted hornpipe, danced with the basic stepping on the toes.

It is widely accepted that dancing to dotted hornpipe spread out from Lancashire. One possible explanation is that it harks back to the "dancing that came before clog dancing." Although it was superceded in time by the even rhythm hornpipe in the cotton areas, it might have persisted elsewhere.

My great uncle, from whom most of my dotted hornpipe steps come, was born in the late 1860's and learnt to clog dance as a boy in the early 1870' s. How advanced his dancing was at this time, I do not known because he subsequently went on the stage and was naturally influenced by the dancing of other professionals. Nonetheless, his dotted Hornpipe had a strong Lancashire flavour in that he used his heels a great deal, including the heel beats of the old heel and toe style. I have come across this in other East Lancashire clog dancers, most notably in a Mr. John Hargreaves, born in the late 1880' s, whose dancing was a mixture of old heel and toe "ground" stepping and "shuffle-on-the-toe high stepping" - danced to dotted hornpipes.

It is also possible that the dotted hornpipe became predominant through the influence of some highly acclaimed performers such as Dan Leno, who is remembered as the greatest clog dancer of all time. He is the most famous example of a traveling performer who became a Music Hall star through his clog dancing. Though he subsequently became a famous comedian and Pantomime Dame at Drury Lane, it was as a clog dancer that he first attracted attention. He was not from the north but a Londoner, caught up in the clog dance craze when the family troupe were touring in Lancashire in 1877, when Dan was seventeen. He subsequently won the title of 'Champion Clog Dancer of the World' seven times, and danced to great acclaim in the theatres. Yet he left no record of his steps beyond saying that the art of clog dancing consisted of "the rolling, the kicking, the taps, the twizzles and the shuffles."

However, research of the late 1950' s, 60' s and 70's brought forward dancers who claimed to have "genuine Dan Leno steps," either taught by him directly, or learnt from someone who had learnt from him, etc. [Ex-ballet dancer, clog dancer and puppeteer Bert Bowden, from Liverpool, taught at least one 'Dan leno' step in the 1990s - CJB.] All of these steps were danced with the basic stepping on the toe to 4/4 dotted hornpipe which at least suggests that his most memorable dances were performed to that rhythm.

A Mr. Proctor of Burnley, who had made dancing clogs for professional dancers in his young days, told me that Dan Leno used a lot of heel beats in his dancing, and my great uncle said that he made use not only of the soles and heels of his clogs, but of the wooden sides of the soles and heels as well. In other words, he used "all the wood" - my great uncle's criterion of clog dancing.

It is always possible that Dan Leno learnt this technique when he learnt to clog dance in Lancashire, though through talent, handwork, inventiveness and sheer professionalism, he took clog dancing to the pinnacle.

| Sailor's Hornpipe |

About the middle of the 18th century, "Sailors' Hornpipes" became popular character dances on stage. Typically, dancers went through the motions of activities on board ship - hauling the ropes, climbing the rigging, looking out to sea, turning the wheel and so on, and dressed themselves in theatrical sailors' costumes.

Dancers, of course, were always on the lookout for novelties, but the popularity of sailors' dances at this particular time seems to have been sparked off by the war against Spain, in which the Royal Navy played a dominant role.

Thomas Arne contributed to the popularity of naval themes by composing the music to the song "Rule Britannia" which had its first performance in 1740. In the same year, London playbills advertised "A Hornpipe in the Character of Jacky Tar" and "A Hornpipe by a Gentleman in the character of a Sailor." Some 20 years later, when the Royal Navy was again prominent, Garrick composed "Hearts of Oak" and a sailor from the Royal Sovereign performed a hornpipe at Drury Lane.

In his book "Folk Dance of Europe", N. A. Jaffé refers to a Provençal dance adapted from a British Sailors' dance which the French called "L'Anglaise" and the Italians "La Via Jarello." One of its features is dancing to the four points of the compass and Jaffé suggests that this might have been the remnant of some ancient ritual intended to protect the sailor as he "Ventured forth on the high seas."

Although "Sailors' Hornpipes" came to prominence on stage, it is highly likely that there were sailors dancing on deck and that, at some point, the stepping and the action imitated life at sea. Many folk dances are occasional [occupational? - CJB] dances. The old Lancashire heel and toe clog dancing has steps using both the rhythm and the actions of the looms and many countries have fishing dances where people dance in patterns to represent making nets, and so on.

In the latter part of the 18'th century the real sailors of the time are depicted in cartoons as wearing striped trousers and wide brimmed, tarred hats, with soft slip-on-shoes on their feet, which suggests that any dancing on deck could have been light and quite athletic. There are records of sailors playing instruments and dancing on board the slave ships, and Captain Cook himself is reputed to have encouraged dancing on deck in the 1770's.

It is interesting that in 1835, a performer called T. P. Cooke or "Tippy", as he was known, who had served on one of Nelson's ships, danced a Sailors' Hornpipe in a play called "Black Eyed Susan". According to J. S. Bratton, writing in the 'Folk Music Journal' 1990 Vol. 6 no.1, T. P. Cooke visited every port on the coast to learn the hornpipe steps he found there and then concocted his own hornpipe. This, of course, does not necessarily mean that he was learning from scratch when he toured the ports. He could just as readily have been looking for new steps to enhance his deck performances for the stage. At any rate, as an actor and hornpipe dancer in nautical plays, he was very popular at the London dockside theatres which were frequented by sailors.

The most accessible record of a "Sailors' Dance" from the 18th century is that of the American dancer John Durang who was born in 1768. He became identified with the "Sailors' Hornpipe" and with the tune composed for him in 1785 and known as "Durang's Hornpipe." The list of steps suggests that his sailors' dance was a mixture of ballet and hornpipe stepping, with a touch of the athletic. Though only 2 of the 22 steps listed suggest a "Sailors' Hornpipe" ("Heel and toe haul back" and "Wave step down") it is possible that he used arm and body movements, not listed, to illustrate the different actions.

In late 19th century Lancashire, when clog dancing was reaching its peak as a "straight dance" and people were looking for novelties, one of the popular novelties was the Clog Sailors' hornpipe. It was danced in the old Heel and Toe style to recognised clog steps which, on their own, would not have suggested a sailors' dance. However, the arm and body movements that accompanied the stepping clearly illustrated figures such as "climbing the rope", "hauling the rope", "the look-out", "tying the knot", "deck drill", "rolling", "ashore", etc.

The last time the Royal Navy inspired a wave of sailor dances was in the 1930's when the fleet was in port. Children in every dancing school in England were tapping out "Sailors' Hornpipes" to songs such as "The Fleet's in Port Again," and "The Fleet's lit up as she rides at anchor," composed at the time. But even in Lancashire the children were wearing tap shoes and dancing on their toes.

| Main references: |

* "The Hornpipe" - George Emmerson. Folk Music Journal, Vol 2 no. 1

* "Folk Dance of Europe" - Nigel Allenby Jaffé, 1990

* "Dancing a Hornpipe in Fetters" - J. S. Bratton, Folk Music Journal 1990, Vol. 6 no. 1

* "Dan Leno" - J. Hickory Wood 1905

* Royal Naval Museum, Portsmouth.

© Pat Tracey 1993

![]()

Email: Chris Brady |

Top # Home | |