Of all the social (and physical!) exercises in colonial life, none bound the

community more closely together than the Ball. Balls took place as soon as there was space

to hold them. Deliberations could go on for months: should Mr and Mrs B. be

invited or was his wife too common? English class divisions could not be applied wholesale

to a colony, and propriety had to be balanced against a universal shortage of women.

At a Freemasons' ball in New Plymouth the 150 people present consisted of "both

Nobs and Snobs". The grandest balls may have been those at Government House

(exquisite examples of ball programmes and dance engagement

cards may be seen in the City of Auckland Public Library), but bachelor balls

did not lag far behind - to say nothing of impromptu dancing that took place after dinner

with the table pushed back and the piano brought forward.

At the

lower end of the scale Lady Barker described a servants' ball at which the music was

provided by one man whistling and another keeping time by clapping together the top

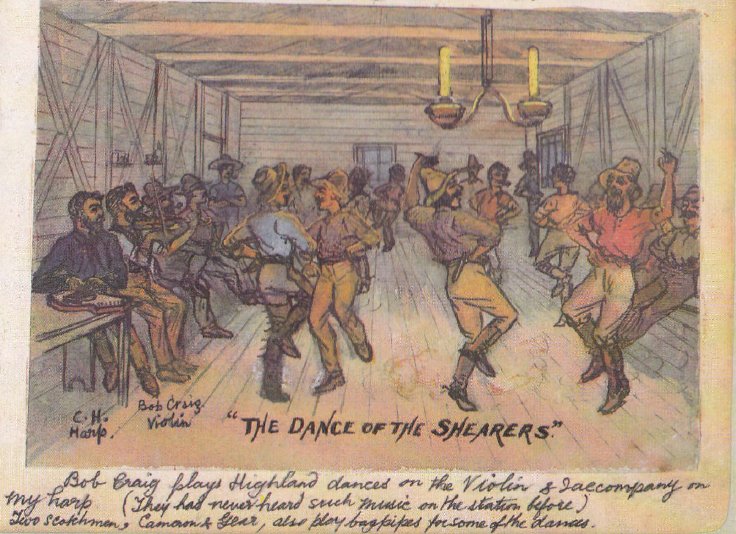

and bottom of her silver butterdish. At Otakapo Station in the Rangitiki in 1894, shearers

had to dance with each other to Bob Craig playing Highland dances on the violin and

Charlie Hammond who drew the scene in his Sketchbook,

Oxford, 1980 of 2 or more couples of male shearers step-dancing to each

other accompanying [them] on his small harp. "They had never heard such

music on the station before". [The dance has been identified by Colin Robertson as

the 'Highland Reel'].

At the

lower end of the scale Lady Barker described a servants' ball at which the music was

provided by one man whistling and another keeping time by clapping together the top

and bottom of her silver butterdish. At Otakapo Station in the Rangitiki in 1894, shearers

had to dance with each other to Bob Craig playing Highland dances on the violin and

Charlie Hammond who drew the scene in his Sketchbook,

Oxford, 1980 of 2 or more couples of male shearers step-dancing to each

other accompanying [them] on his small harp. "They had never heard such

music on the station before". [The dance has been identified by Colin Robertson as

the 'Highland Reel'].

The astonishing thing is the energy summoned forth, for balls usually lasted from early

evening until dawn or even later. Respite from the vigorous inside could be had on

the verandah, which was also the venue for flirting - wives could be on recognised

"flirting terms" with other gentlemen. Charlotte Godley described how completely

exhausted dancers dragged themselves home as the sun rose, the women to sleep, the men to

go straight to the farm.

The names of the dances have the patina of history; quadrilles, polkas, schottisches

and galops have all gone and only the waltz remains.

What were the dances like? When "a square, fat, dirty-looking man with a large

grey head", a contract butcher of Wellington, asked Charlotte Godley if she would

dance a galop with him (he had taken the precaution of discovering that it was

not difficult), she declined. Whereupon he pressed her for a quadrille which she felt

obliged to dance: "I got through it safely notwithstanding his wonderful

evolutions and prancings".

The quick galop, a couple dance in 2/4 time, either ended the first half of the

entire evening. Made up of very simple gliding steps with occasional turning movements, a

glide became a sprint during the final notes as the couples rushed towards the chairs

along the walls.

The quadrille, similar to the square dance, gave excellent opportunities for

conversation and frequent exchange of partners. The sets could become so elaborate it

needed someone to call out the figures. The "Lancers" was a longer-surviving

variant. At an amazing ball across the bay from Lyttleton in 1851, Charlotte Godley tells

of a Mrs. Russell who danced 40 times and wore out the only tidy pair of thin boots

she had, a colonial calamity, and of a Mrs. Fitzgerald who left after five in the morning

"with a delapidated dress and her hair all danced down".

The other dances of the period, apart from the waltz, were the lively polka, in 2/4

time with short heel and toe steps; the schottische, sometimes described as a slow

polka; and the reel, survivor of the English, Scottish and Irish country dances. Not every

ball had the services of a military band, so music was provided by ensembles of every hue

- pianos, violins, flutes and flageolets.

The Atheneum in the capital (of New Zealand) was described as "the

Almack's of Wellington", differing markedly from London's famed dance hall in

the amount of dust which enveloped the dancers.

Thomas Hardy, the poet, had many a vigorous evening at Almack's, as he did at the

Argyle and Cremorne Gardens:

Who now remembers gay Cremorne,

And all its jaunty jills,

And those wild whirling figures born

Of Julien's grand quadrilles ... '

And the gas-jets winked, and the

lustres clinked,

And the platform throbbed as with

arms linked

We moved to the Minstrelsy. |

J.M.Thompson

Then in the early 1900s, English 'folk dancing' as defined by collector and teacher

Cecil Sharp was brought over by migrants from the UK and taught widely, especially from

the 1920s onwards. Disciples of Sharp such as one Miss.

Hilda Taylor emigrated to NZ and helped to create a thriving folk dance movement

throughout the country.

In the 1920s and 1930s one John Oliver, a New Zealander at Cambridge University, was

also involved in promoting English country dancing with 'The Round' - a somewhat exclusive

country dance club at Cambridge; and he was also a member of Cambridge Morris Men and the

Travelling Morrice - see 'The Round' -

History. When he returned to NZ he was instrumental in promoting English folk dancing

including Sharp-style English country dancing and also morris and sword dancing.

The New Zealand Society for English Folk Dancing was the first official overseas branch

of the EFDSS. Indeed in New Zealand during the 1930s/40s there were more English country

dance groups than Scottish. But there were few men involved. It's magazine English Folklore in Dance and Song can be read here.

Two of the ECD clubs existed even as late as the 1980s/90s - these were in

Timaru and Christchurch. The ladies of Christchurch were filmed in the 1980s and can be

seen on YouTube.

This dance is somewhat remarkable in that it was newly composed in

England when prevailing attitudes were that Sharp's interpretations of the Playford

country dances were the only ones to be taught and performed.

![]()

![]()